Case Series

- Dr. Faizan Ahmed ID 1

- Muhammad Abdullah ID 2

- Bilal Qammar ID 3

- Madeeha Shafqat ID 4

- Anika Goe ID 5

- Muhammad Shees Hunain ID 2

- Muhammad Faizan Tahir ID 2

- Tehmasp Mirza ID 2

- Haris Bin Tahir ID 6

- Swapnil Patel ID 1

- Amir Hossain ID 1

- Fawaz Alenezi ID 7

- Mohammad Bakr1 ID 1

1 Jersey Shore University Medical Centre, Neptune, NJ, USA

2 Shalamar Medical and Dental College, Lahore, Pakistan

3 Trauma and Orthopedic surgery, Sir Ganga Ram hospital, Lahore, Pakistan

4 Geisinger Medical Center Danville, PA

5 Kakatiya Medical College, Warangl, Telangana, India.

6 Lahore General Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan

7 Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, US

*Corresponding Author: Dr. Faizan Ahmed, Jersey Shore University Medical Centre, Neptune, NJ, USA.

Citation: Dr. Faizan Ahmed , Muhammad Abdullah, Bilal Qammar, Madeeha Shafqat, Anika Goel, Muhammad Shees Hunain, Muhammad Faizan Tahir, Tehmasp Mirza, Haris Bin Tahir, Mohammad Bakr, Swapnil Patel, Amir Hossain, Fawaz Alenezi. Is Influenza an Underrecognized Driver of Cardiovascular Mortality in the United States? A 25-Year Comprehensive Subgroup Analysis of Epidemiologic Trends, Disparities, and ARIMA-Based Mortality Forecasting (1999–2023), J Clinical and Medical Research and Studies, V (5)I(1), DOI: 1

Copyright: 2026 Dr. Faizan Ahmed. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: December 28, 2025 | Accepted: January 16, 2026 | Published: January 18, 2026

Abstract

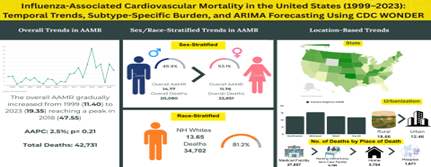

Influenza infection has been associated with acute cardiovascular complications: however, population level patterns of influenza-associated cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality remains underexplored. This study aimed to evaluate temporal trends, demographic disparities, and geographic variations in influenza-associated cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality in the United States over 25 years. A population-based observational analysis was conducted using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) Multiple Cause of Death database (1999–2023). Adults aged 45 years and older whose death certificates listed both influenza and CVD were included. Cardiovascular mortality was identified using ICD-10 codes I00–I99, and influenza-related mortality using J09–J11. Age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) per million population were calculated using the 2000 U.S. standard population. Temporal trends were analyzed using Joinpoint regression to estimate annual percentage change (APC) and average annual percentage change (AAPC) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). From 1999 to 2023, a total of 42,731 deaths were attributed to influenza-related CVD. AAMRs increased from 11.4 per million in 1999 to 19.35 per million in 2023, peaking at 47.55 per million in 2018. The overall AAPC was 2.53 (95% CI: –1.71–7.43; p = 0.21). Heart failure accounted for the highest number of deaths (11,611), followed by coronary ischemic heart disease (9,746) and acute myocardial infarction (4,227). Males had higher absolute mortality, whereas females demonstrated a greater relative increase (AAPC = 6.72; p < 0.001). Mortality was highest among individuals aged 65 years and older, in southern regions, and in rural counties. Forecasting predicts continued increases in AAMR through 2035. Influenza infection remains a significant contributor to cardiovascular mortality in the United States. Trends align with findings from Ouranos et al. (2023), who reported a 9.9% cumulative incidence of cardiovascular complications among hospitalized influenza patients.

Keywords: Influenza; cardiovascular mortality; epidemiologic trends

Case Series

Introduction:

Influenza, a highly infectious viral respiratory infection, continues to have important public health consequences globally, and is also linked with large annual morbidity and mortality, especially among the elderly and in patients with chronic comorbidities[1,2]. While the effect of influenza on the respiratory system is firmly established, there is growing evidence from literature that influenza infection has effects on the cardiovascular system. Mechanisms that include viral replication and subsequent systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and a state of hypercoagulability can cause acute cardiovascular events[3]. All of these indirect mechanisms are responsible for increased mortality risk in individuals with pre-existing cardiovascular disease (CVD) and increase the profile of influenza as an underrated but powerful precipitant of cardiovascular events.

During the past 20 years, the impact of influenza on cardiovascular mortality has been investigated in both observational and mechanistic studies. Most notably, research that has been conducted based on population data shows evidence of elevated cardiovascular hospitalization or deaths as it coincides with seasonal rises in influenza[1,3]. Furthermore, randomized trials and meta-analyses that have assessed cardiovascular protective benefits of the influenza vaccine in terms of reduction of major adverse cardiovascular events, especially in those with pre-existing CVD, indicate prevention of cardiovascular events can be achieved using vaccine-based therapy[4]. Together, these studies demonstrate influenza infection is systemic and can precipitate cardiovascular events, and even possibly prevent them using vaccination.

Nevertheless, in spite of these results, the majority of earlier research was short-term, took place in a single influenza season or hospital-cased cohort and depended on mortality data lacking dual cause of death ratings. Therefore, the overall picture of influenza-associated cardiovascular mortality is predominantly uncharted, most notably in national real-world datasets. Sociodemographic group-related factors, geographic locations or urbanization levels, etc., usually are not considered in order to describe experience with dual coded mortality for influenza associated cardiovascular mortality during any period of time. Given the aging US population and the evolving burden of influenza and cardiovascular disease, it is critical and opportune to fill this gap in knowledge. Understanding the long-term mortality experience for individuals with concomitant influenza and cardiovascular disease is important for guiding a coordinated public health response, not the least of which is crafting vaccination policy, but also in pandemic planning and risk communication for vulnerable groups [5].

This present study aims to examine data in a 22-year retrospective study based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) Multiple Cause of Death (MCD) dataset. Our analysis will systematically quantify the temporal trends of dual-coded influenza-associated cardiovascular mortality, examine demographic and geographic disparities, and provide new evidence of the shared association between viral respiratory illness and cardiovascular mortality in the adult population of the US.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This study was a population-based observational analysis using the publicly available Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) Multiple Cause of Death (MCD) database from 1999 to 2023. The population consisted of adults aged 45 years and older whose death certificates listed both cardiovascular disease (CVD) and influenza as contributing causes of death. Cardiovascular mortality was identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes I00–I99, which represent diseases of the circulatory system. Concurrently, influenza-related mortality was identified using ICD-10 codes J09 (Influenza due to identified avian influenza virus), J10.0–J10.8 (influenza with pneumonia or other respiratory manifestations, virus identified), and J11.0–J11.8 (influenza with pneumonia or other manifestations, virus not identified). By intersecting these two groups of ICD codes, the analysis captured decedents for whom both cardiovascular and influenza-related pathology contributed to mortality.

Data Source and Stratification

The data were extracted from the CDC WONDER Multiple Cause of Death database, which provides access to U.S. mortality and population data for public health surveillance and research [6]. The database contains information on year of death, demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), and geographic identifiers. Age was categorized into five 10-year groups: 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84, and 85+ years. Sex was recorded as male or female based on death certificates. Race/ethnicity was classified into Hispanic and non-Hispanic populations, with non-Hispanic further subdivided into White and Black or African American. Due to inconsistent or low-count data, non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander and non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native groups were excluded. Geographic stratification included census regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau [7]. Urbanization was assessed using the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Urban–Rural Classification Scheme, which categorizes counties into six levels: Large Central Metro, Large Fringe Metro, Medium Metro, Small Metro, Micropolitan (Nonmetro), and NonCore (Nonmetro) [8]. Place of death was grouped into Medical Facility, Decedent’s Home, Hospice, Nursing Home/Long-Term Care, Other, and Unknown.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was the age-adjusted mortality rate (AAMR) per 100,000 individuals for influenza-associated cardiovascular deaths, computed using the 2000 U.S. standard population. Rates were calculated per 1,000,000 people to enhance interpretability due to the lower incidence of co-coded causes. Joinpoint regression analysis was performed using the Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 5.3.0 (National Cancer Institute), to assess temporal trends in AAMR from 1999 to 2020 [9]. The Annual Percentage Change (APC) and Average Annual Percentage Change (AAPC) were estimated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Monte Carlo permutation method was used to test for statistical significance of changes in trends over time [10]. The Weighted Bayesian Information Criterion (WBIC) was used to determine the optimal number of joinpoints. A p-value <0>

Exploratory time-series forecasting analyses were additionally performed to examine potential future patterns in influenza-associated cardiovascular mortality. Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models were implemented using Python (version 3.13.2) and the statsmodels package. Model parameters (p, d, q) were iteratively tested, and the best-fitting model was selected based on minimization of root mean square error (RMSE) during internal validation [11]. These forecasts were exploratory in nature, were not intended for causal inference or policy prediction, and were interpreted cautiously given the observational design and inherent uncertainty of extrapolating beyond observed data.

Ethical Considerations

The analysis used publicly available, de-identified data, exempting it from institutional review board approval. All potentially identifiable or incomplete records were excluded to maintain privacy. The study was conducted for public health and epidemiological purposes only, in accordance with the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. 242m(d)). No external funding was received, and the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Results:

OVERALL

Influenza related cardiovascular disease (CVD) caused a total of 35260 deaths in the US from 1999 to 2020 and an additional 7471 deaths from 2021 to 2023 resulting in a total 42731 deaths. The age adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) ranged between 11.4 per million (95% CI 10.72-11.08) in 1999 to 19.35 per million (95% CI 18.64-20.07) in 2023. The highest AAMR per million was reported in 2018 at 47.55. The average AAMR for 1999-2020 reported to be 13.53 per million (95% CI 13.39-13.67) and 16.98 per million (95% CI 16.59-17.37) for years 2021-2023. These trends highlight large variations in AAMR in different time periods with an average annual percentage change (AAPC) of 2.53* (95% CI -1.71 – 7.43) (p-value < 0>

CVD was further segregated into Heart Failure (HF), Coronary Ischemic Heart Disease (CIHD) and Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) to show correlation between each of these with influenza. Mortality trends assessments from 1999-2023 revealed HF had the most deaths (11,611), followed by CIHD (9,746) and finally AMI (4,227). CIHD had the greatest AAPC of 4.92 (95% CI 2.13-10.43) (p value<0 xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed>

Figure 1 Overall Influenza and CVD-related AAMR per 1,000,000 in the United States, 1999 to 2023

GENDER

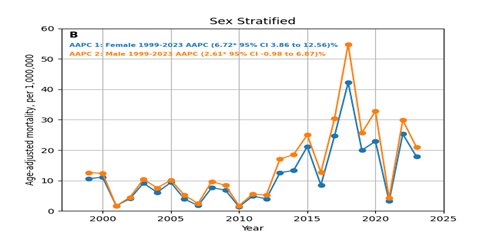

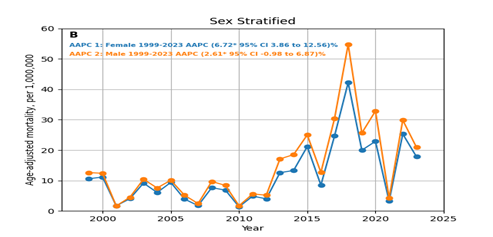

Segregation of the database by gender shows mirrored trends for both the groups but males had consistently higher AAMR compared to females. Male population had a total of 20080 deaths and the female population had a total of 22651 deaths from 1999 to 2023, respectively. The AAMRs for males was recorded to be 15.74 per million (95% CI 15.5-15.98) for years 1999-2020 and 18.57 per million (95% CI 17.95-19.19) for 2021-2023. AAMRs for females was recorded to be 11.95 per million (95%CI 11.78-12.13) for years 1999-2020 and 15.68 per million (95%CI 15.18-16.18) for 2021-2023. The highest AAMR per million for males was recorded in 2018 at 54.75 (95% CI 52.83-56.67) and for females at 42.22 (95% CI 40.79-43.64) in 2018. Mortality trends increased in both genders from 1999-2023 however females had a much higher AAPC of 6.72* (95% CI 3.86-12.56) (p value < 0>

Figure 2 Sex-stratified Influenza and CVD-related AAMRs per 1,000,000 in the United States, 1999 to 2023

RACE / ETHNICITY

Data for Mortality trends for Influenza related CVD was divided into two main categories: HISPANIC or LATINO and NON-HISPANIC ORIGIN which included four races (American Indians or Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, Black or African American, White). AAMRs for American Indians, Asians and Blacks were mostly unavailable. From the available data it can be seen that the highest AAMR per million for Asians was 32.22 (95% CI 27.81-36.62) in 2018, 42.14 (95% CI 38.73-45.54) per million in 2020 for Blacks, 50.94 (95% CI 49.58-52.31) per million in 2018 for whites, and 35.37 (95% CI 32.19-38.54) per million in 2020 for Hispanics. AAPCs could not be compared due to unavailability of data except for in Whites where AAPC was 2.18 (95% CI -2.36--6.97) (p value < 0>

The data for race reveals an even more interesting trend where AAMR in 2021 falls so low that data is unavailable for NH American Indians and Blacks while for other races and Hispanics it is in the single digits.

Figure 3 Race/ Ethnicity Stratified Influenza and CVD-related AAMR per 1,000,000 deaths in the United States, 1999 to 2023

AGE GROUPS

The mortality trends for Influenza related CVD were divided into the two main groups, population (45-64 years) and population (65+). The total number of deaths in these age groups are as follows: for age groups 45-64 8014 deaths between 1999-2023, for age groups 65+ 34717 deaths between 1999-2023. The AAMRs varied widely between these age groups i.e. 3.66 per million (95% CI 3.57-3.75) for population (45-64 years) in 1999-2020 and 5.36 per million (95% CI 5.08-5.65) in 2021-2023 {with the highest AAMR of 11.93 per million (95%CI 11.2-12.65) in 2020} , for population (65 +) 30.88 in 1999-2020 (95%CI 30.52-31.24) and 37.38 in 2021-2023 (95%CI 36.43-38.34) {with the highest AAMR of 110.35 per million (95%CI 107.44-113.26) in 2018} , respectively. Both age groups had rise in mortality trends however AAPC was higher for age group 45-64 respectively with an AAPC of 10.29* (95% CI 7.52 – 16.97) (p value < 0>

GEOGRAPHICAL REGIONS (CENSUS & STATES)

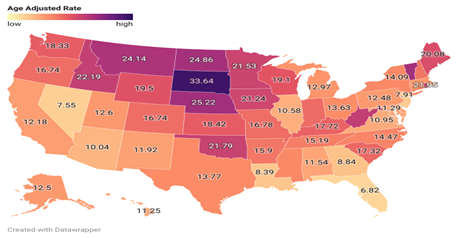

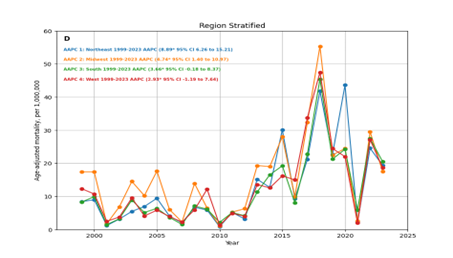

Mortality trends for Influenza related CVD were segregated into four geographical areas i.e. Northeast, Midwest, South and Western regions. The highest number of casualties occurred in South (14,406) deaths, followed by Midwest (11,116), West (9,066) and Northeast (8,143) from 1999 to 2023. The highest average AAMR was recorded in the Midwest at 16.03 (95% CI 15.7-16.35) per million in 1999-2020 while the highest average AAMR in 2021-2023 was in the South region reported as 18.17 (95% CI 17.51-18.82) per million. South region had the lowest average AAMR 12.15 per million (95% CI 11.93-12.37) in 1999-2020 and Northeast with lowest in 2021-2023 with average AAMR of 15.57 per million (95%CI 14.71-16.43) Each region had a rise in AAPCs however Northeast had the maximum rise with AAPC 8.89* (95% CI 6.26-15.21)(p value<0>

From 1999–2020, the highest AAMR for Influenza-associated CVD was observed in South Dakota, with an AAMR of 33.64 per million and a total of 278 deaths, ranking at the 100th percentile among all U.S. states. The lowest AAMR was noted in the District of Columbia, with 27 deaths and an AAMR of 5.72 per million at the 0th percentile. The average AAMR across all states during this period was approximately 13.53 per million, with a cumulative total of 35,260 deaths. States with mortality rates at or above the 90th percentile included South Dakota, Nebraska, Vermont, North Dakota, Montana, and West Virginia, whereas those at or below the 10th percentile included Georgia, Louisiana, New Jersey, Nevada, Florida, and the District of Columbia.

From 2021–2023, the highest AAMR Influenza related CVD was reported in Oklahoma, with 216 deaths and an AAMR of 41.65 per million, ranking at the 100th percentile. The lowest reliable estimate was seen in New Jersey, with 134 deaths and an AAMR of 10.46 per million, ranking at the 0th percentile. Several states, including Alaska, Delaware, Wyoming, and the District of Columbia, had unreliable or suppressed data due to small sample sizes. The average AAMR across all states was unavailable. States at or above the 90th percentile included Oklahoma, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Dakota, and Montana, while those at or below the 10th percentile were Hawaii, Arizona, Connecticut, and New Jersey.

Figure 4 State-Stratified Influenza and CVD-related AAMRs per 1,000,000 in United States 1999-2020

Figure 5 Influenza and CVD-related AAMR per 1,000,000 Stratified by Regions in the United States, 1999 to 2023

Urbanization

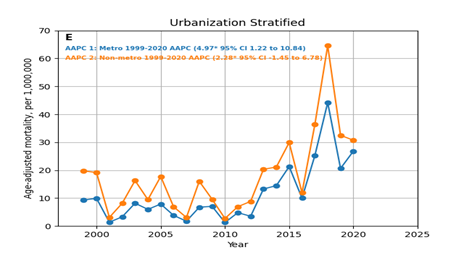

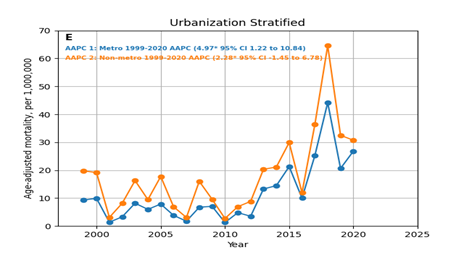

Data for urbanization revealed that in the years 1999-2020 Urban areas had the larger number of deaths 26,718 with the average AAMR 12.46 per million (95% CI 12.31-12.61) and the highest AMR reported in 2018 at 44.19 per million (95% CI 42.97-42.54). Rural areas had 8,542 deaths in these years with the average AAMR 18.66 per million (95% CI 18.27-19.06) and the highest AAMR reported in 2018 at 64.57 per million (95% CI 61.27-67.88). Both Urban and Non-Urban areas had significant increase in mortality rates with AAPCs of 4.97* (95% CI 1.22-10.84) (p value <0>

Figure 6 Urbanization Stratified Influenza and CVD-related AAMR per 1,000,000 in the United States, 1999 to 2023

Place of Death

Database trends from 1999-2023 showed that medical facility in-patient had the greatest number of deaths (25,534), with the highest number of deaths in 2018 (4025) and lowest number of deaths in 2001(61). It was followed by Nursing Home (6,786), Decedent’s Home (5,754), and Hospice Facility (1,671),

Forecast

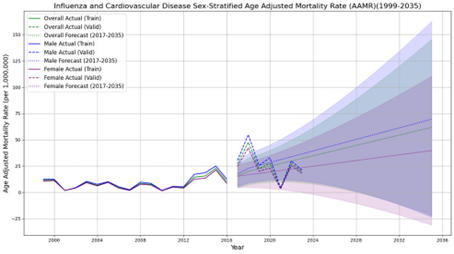

Forecasting database trends till 2035 reveals rising mortality trends with Overall AAMR peaking at 61.77 in 2035 (-22.04 – 145.58). Trends forecasted based on gender shows a similar trend and significant rise in AAMRs peaking in 2035 to 69.5 per million (95% CI -23.67 – 162.68) for males and 39.66 (95% CI -31.17 – 110.49) in females. Overall mortality trends increased significantly till 2035 with AAPCs of 5.38 (95% CI: 5.32 – 5.43; p < 0>

Figure 7 ARIMA Future Forecast of Influenza and CVD-related AAMR per 1,000,000 in the United States, 1999 to 2023

Discussion:

This national population-based study spanning 1999–2023 provides compelling population-level evidence of temporal patterns and disparities that influenza-associated cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a substantial contributor to mortality in the United States. By leveraging CDC WONDER mortality data, our analysis highlights pronounced fluctuations in influenza-related cardiovascular deaths across time, demographic groups, and geographic regions. The findings charatcerize co-occurring influenza and cardiovascular mortality trends and their evolution over major public health events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Over 42,000 influenza-related CVD deaths were identified during the study period, emphasizing the public health relevance of this intersection between infectious and cardiovascular conditions. The increase in age-adjusted mortality rate (AAMR) from 11.4 per million in 1999 to 19.35 per million in 2023, peaking at 47.55 per million in 2018, reflects the recurring periods of severe influenza epidemics rather than a monotonic rise. The upward inflection observed between 2010 and 2018, characterized by a positive annual percentage change (APC) of 27.47, coincided with years dominated by influenza A(H3N2) strains, which are known for higher virulence and poorer vaccine effectiveness. These data are consistent with prior epidemiologic observations that severe influenza seasons coincide with spikes in all-cause and cardiac mortality [12].

The sharp dip in 2021 (AAMR = 3.68 per million) represents an epidemiological outlier and likely reflects the suppression of influenza circulation during the COVID-19 pandemic due to non-pharmaceutical interventions such as masking and social distancing. Reduced influenza testing and diagnostic displacement under SARS-CoV-2 coding further explain the decline. The subsequent rebound in 2022–2023, as influenza activity normalized, validates this interpretation. These oscillations highlight the sensitivity of influenza-associated cardiovascular mortality to both viral ecology and health system disruptions. When analyzed by subtype, heart failure (HF) accounted for the greatest number of influenza-associated deaths, followed by coronary ischemic heart disease (CIHD) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) [13]. This gradient aligns with the pathophysiological vulnerability of individuals with pre-existing myocardial dysfunction. HF mortality rose sharply between 2010–2018, paralleling increased influenza severity during those years. CIHD, however, demonstrated the highest average annual percentage change (AAPC 4.92; p < 0>

Interestingly, AMI mortality exhibited a biphasic pattern declining through 2011, surging by 2018, then decreasing post-2018 mirroring both influenza virulence cycles and evolving cardiovascular care quality. These findings collectively suggest that influenza infection may act as a precipitating factor in susceptible individuals, particularly during high-virulence seasons [15].

The present findings complement and extend those of Ouranos et al. (2023), [16] who conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 6,936 hospitalized patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza to quantify the cumulative incidence and in-hospital mortality of cardiovascular complications. They reported a 17.47% cumulative incidence of heart failure, 2.19% for AMI, 6.12% for arrhythmias, 2.56% for myocarditis, and 1.14% for stroke or TIA, with an overall in-hospital cardiovascular mortality rate of 1.38%. Our analysis, though population-level and mortality-focused rather than hospital incidence-based, converges on similar conclusions: influenza infection may carry a clinically meaningful cardiovascular burden, with HF and ischemic events predominating. While Ouranos et al. measured in-hospital cardiovascular complications during acute infection, our findings capture population-level mortality perspective based on death certificate data, capturing both acute and post-infectious outcomes . The considerably lower absolute mortality rate in our dataset compared to the meta-analysis’s in-hospital figures can be attributed to denominator differences in population-wide mortality per million versus patient-level incidence among hospitalized cases. However, both datasets underscore the same hierarchy of risk: heart failure as the most frequent manifestation, followed by ischemic and arrhythmic complications. Importantly, the meta-analysis demonstrated a near 10% cumulative rate of cardiovascular events among hospitalized influenza patients, supporting the biological plausibility of the long-term population-level mortality burden observed in this study [17]. The parallel trends between our longitudinal U.S. mortality data and the pooled international hospital data suggests that cardiovascular surveillance should be considered during influenza management.

Our results also reveal sex-specific differences, with males exhibiting higher absolute AAMRs but females showing a sharper proportional rise (AAPC = 6.72; p < 0>

The higher AAMR observed in rural compared to urban populations (18.66 vs. 12.46 per million) likely results from healthcare access disparities, fewer vaccination campaigns, and delayed recognition of influenza complications [25]. The predominance of deaths in inpatient medical settings underscores that influenza-associated cardiovascular events often culminate in acute hospital presentations, consistent with Ouranos et al.’s hospital-based analysis. The substantial proportion of deaths at home or in long-term care facilities emphasizes missed opportunities for diagnosis or timely intervention among frail populations. Chow et al. (2020), showed that one in eight hospitalized adults with influenza experienced an acute cardiovascular event, most commonly HF decompensation or myocardial ischemia. Likewise, the NEJM study by Kwong et al. (2018) demonstrated a six-fold increase in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) risk within one week of laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. Beyond acute ischemia, Sellers et al. (2017) detailed a spectrum of extrapulmonary complications, including myocarditis, arrhythmias, and vascular inflammation, resulting from viral invasion and systemic immune activation. Experimental evidence by Wu and Huang (2017) provided mechanistic support, showing that influenza infection synergistically upregulates matrix metalloproteinase-9 and pro-inflammatory cytokines in endothelial cells exposed to oxidized LDL, promoting plaque instability. The significant post-2010 increases in HF- and CIHD-related mortality observed in our data align with these mechanistic pathways. Exploratory mortality forecasting through 2035 suggests a continuing upward trend, with projected AAMRs exceeding 60 per million. Though, the projections should be interpreted with caution, they mirrors global predictions that aging populations and persistent cardiovascular comorbidity will amplify influenza’s cardiac impact unless vaccination rates improve. Integrating annual influenza vaccination into cardiovascular prevention frameworks especially for patients with heart failure or coronary artery disease could significantly reduce both infection-related morbidity and cardiovascular mortality. Clinical trials have shown that influenza vaccination can lower major adverse cardiac events by 15–45%, positioning it as a low-cost, high-impact intervention [26-29].

Limitations

This study’s strengths include its nationwide scope, long follow-up period, and rigorous trend analysis using Joinpoint regression, enabling nuanced detection of shifts in mortality over time. However, limitations include reliance on death certificate data, which may underestimate influenza contribution, and inability to distinguish between direct viral cardiac injury and indirect triggers of decompensation. In contrast to the meta-analysis by Ouranos et al., which captured only hospitalized and laboratory-confirmed cases, our study cannot confirm influenza infection status at the individual level but provides broader external validity by encompassing the entire population.

Conclusions

This nationwide analysis spanning more than two decades demonstrates persistent and heterogeneous population-level associations between influenza and cardiovascular mortality in the United States, particularly among older adults and those with underlying heart failure or ischemic heart disease. The study revealed temporal associations in mortality, with peaks corresponding to severe influenza seasons, and a transient decline during the COVID-19 pandemic suggestive of reduced viral circulation and diagnostic displacement. Sex-based, racial, and regional disparities highlight that influenza’s cardiovascular impact is not evenly distributed. Males exhibited higher absolute mortality rates, while females showed a faster rate of increase. Similarly, rural populations and southern regions experienced greater mortality, underscoring the influence of access to care and vaccination coverage. The younger adult population (45–64 years) demonstrated a steeper rise in mortality, indicating a shifting epidemiologic burden that parallels increasing cardiometabolic risk factors in middle age. Future studies incorporating individual-level clinical data are needed to clarify causal pathways and inform targeted interventions.

Supplementary Data

Supplemental Table 1: Number of Influenza and CVD-Related Deaths, Stratified by Sex and Race in Adults in the United States 1999-2023.

| Year | Overall | Women | Men | NH American Indian or Alaskan Native | NH Asian or Pacific Islander | NH Black or African American | NH White | Hispanic or Latino | Population |

| 1999 | 1075 | 651 | 424 | Suppressed | 13 | 52 | 975 | 30 | 95153686 |

| 2000 | 1124 | 688 | 436 | Suppressed | 11 | 48 | 1034 | 24 | 96944389 |

| 2001 | 168 | 104 | 64 | 0 | Suppressed | 15 | 145 | Suppressed | 99781854 |

| 2002 | 420 | 257 | 163 | Suppressed | Suppressed | 15 | 386 | 10 | 102217733 |

| 2003 | 978 | 585 | 393 | Suppressed | Suppressed | 41 | 900 | 20 | 104692428 |

| 2004 | 679 | 393 | 286 | Suppressed | Suppressed | 33 | 630 | Suppressed | 107138553 |

| 2005 | 1014 | 626 | 388 | Suppressed | Suppressed | 37 | 941 | 22 | 109787199 |

| 2006 | 467 | 258 | 209 | Suppressed | Suppressed | 13 | 437 | 11 | 112380379 |

| 2007 | 221 | 117 | 104 | Suppressed | Suppressed | Suppressed | 197 | Suppressed | 114894084 |

| 2008 | 950 | 537 | 413 | Suppressed | Suppressed | 46 | 868 | 20 | 117395131 |

| 2009 | 893 | 448 | 445 | 15 | 28 | 76 | 645 | 127 | 119895863 |

| 2010 | 182 | 91 | 91 | 0 | Suppressed | 21 | 132 | 24 | 121757429 |

| 2011 | 636 | 358 | 278 | Suppressed | 12 | 50 | 524 | 43 | 124174484 |

| 2012 | 552 | 302 | 250 | Suppressed | 11 | 33 | 485 | 18 | 126000296 |

| 2013 | 1840 | 967 | 873 | Suppressed | 50 | 136 | 1543 | 108 | 127788037 |

| 2014 | 2024 | 989 | 1035 | 14 | 45 | 167 | 1612 | 180 | 129779643 |

| 2015 | 3005 | 1700 | 1305 | 26 | 74 | 168 | 2608 | 116 | 131826832 |

| 2016 | 1383 | 651 | 732 | Suppressed | 49 | 118 | 1082 | 122 | 133494018 |

| 2017 | 3727 | 2021 | 1706 | 16 | 112 | 239 | 3115 | 241 | 135229289 |

| 2018 | 6677 | 3477 | 3200 | 42 | 210 | 523 | 5505 | 387 | 136335528 |

| 2019 | 3239 | 1646 | 1593 | 39 | 113 | 294 | 2548 | 240 | 137381702 |

| 2020 | 4006 | 1882 | 2124 | 35 | 204 | 622 | 2615 | 509 | 138429175 |

| Total | 35260 | 18748 | #### | 187 | 932 | 2747 | 28927 | 2252 | 2622477732 |

| 2021 | 528 | 254 | 274 | Suppressed | 16 | 69 | 378 | 61 | 139339453 |

| 2022 | 4061 | 2147 | 1914 | 47 | 95 | 367 | 3192 | 325 | 140311934 |

| 2023 | 2882 | 1502 | 1380 | 31 | 67 | 286 | 2205 | 252 | 141596553 |

| Total | 7471 | 3903 | 3568 | 78 | 178 | 722 | 5775 | 638 | 421247940 |

Supplemental Table 2: Annual Percent Change (APC) and Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) of Influenza and CVD–related Age-Adjusted Mortality Rates per 1,000,000 in Adults in the United States 1999-2023

| Year | AAPC (95% CI) | Year2 | APC (95% CI) |

| Overall | 1999-2010 | -5.7855 (-45.4072 to 6.4338) | |

| 1999-2023 | 2.5375(-1.711 to 7.4338) | 2010-2018 | 27.4787* (15.718 to 111.7039) |

| 2018-2023 | -12.8075 (-45.8534 to 0.6192) | ||

| Female | 1999-2023 | 6.7284* (3.8658 to 12.5675) | |

| 1999-2023 | 6.7284*(3.8658 to 12.5675) | ||

| Male | 1999-2010 | -5.3284 (-41.4982 to 5.6233) | |

| 1999-2023 | 2.615(-0.989 to 6.8763) | 2010-2018 | 27.8763* (16.6298 to 86.6793) |

| 2018-2023 | -13.8479* (-37.8057 to -3.0152) | ||

| NH Asian | 2013-2018 | 31.0449* (12.4133 to 215.3718) | |

| 2013-2023 | 4.1039(-8.5372 to 25.8289) | 2018-2023 | -17.2985* (-46.921 to -3.5611) |

| NH Black | 2008-2020 | 21.7616* (16.6457 to 55.6059) | |

| 2008-2023 | 11.3880*(5.4247 to 25.9688) | 2020-2023 | -21.9898 (-61.267 to 4.7568) |

| NH White | 1999-2010 | -6.1661 (-43.4076 to 6.0577) | |

| 1999-2023 | 2.1803(-2.3653 to 6.9723) | 2010-2018 | 27.6163* (15.5683 to 114.7288) |

| 2018-2023 | -13.6382 (-50.1066 to 0.5991) | ||

| Hispanics | 2008-2023 | 7.8199* (1.289 to 20.6212) | |

| 2008-2023 | 7.8199*(1.289 to 20.6212) | ||

| Northeast | 1999-2023 | 8.8995* (6.2608 to 15.2161) | |

| 1999-2023 | 8.8995*(6.2608 to 15.2161) | ||

| Midwest | 1999-2023 | 4.7477* (1.4058 to 10.9712) | |

| 1999-2023 | 4.7477*(1.4058 to 10.9712) | ||

| South | 1999-2010 | -5.0634 (-42.606 to 6.7563) | |

| 1999-2023 | 3.6686(-0.1879 to 8.3786) | 2010-2018 | 28.6197* (17.5643 to 101.8486) |

| 2018-2023 | -10.9034 (-36.7406 to 0.9939) | ||

| West | 1999-2011 | -3.796 (-42.9604 to 6.7697) | |

| 1999-2023 | 2.934(-1.1952 to 7.6436) | 2011-2018 | 31.6394* (18.1279 to 104.1323) |

| 2018-2023 | -14.2015* (-42.8277 to -2.5348) | ||

| Metro | 1999-2010 | -5.4161 (-36.0146 to 9.2063) | |

| 1999-2020 | 4.9721*(1.2201 to 10.8469) | 2010-2018 | 29.7613* (7.2072 to 103.2075) |

| 2018-2020 | -20.2556 (-44.5107 to 17.3215) | ||

| Non-Metro | 1999-2011 | -5.666 (-24.9686 to 3.8079) | |

| 1999-2020 | 2.2848(-1.4582 to 6.7816) | 2011-2018 | 30.3951* (14.3987 to 93.0621) |

| 2018-2020 | -28.9454 (-53.5228 to 11.0449) | ||

| 45-64 | 1999-2023 | 10.2997* (7.5246 to 16.9782) | |

| 1999-2023 | 10.2997*(7.5246 to 16.9782) | ||

65+ | 1999-2010 | -7.4558 (-44.3114 to 4.7315) | |

| 1999-2023 | 1.5821(-2.6829 to 6.2991) | 2010-2018 | 28.5890* (15.9451 to 119.9763) |

| 2018-2023 | -14.4877* (-45.6876 to -0.7809) | ||

| HF | 1999-2010 | -7.1102 (-43.1539 to 5.3676) | |

| 1999-2023 | 2.4207(-1.687 to 7.2758) | 2010-2018 | 29.8795* (17.2001 to 122.0293) |

| 2018-2023 | -13.1707* (-43.3655 to -0.4297) | ||

| CIHD | |||

| 1999-2023 | 4.9265*(2.1337 to 10.4304) | 1999-2023 | 4.9265* (2.1337 to 10.4304) |

| AMI | 1999-2011 | -4.9733 (-29.9861 to 3.899) | |

| 1999-2023 | 0.4257(-3.3475 to 4.0349) | 2011-2018 | 26.9382* (13.4571 to 86.3437) |

| 2018-2023 | -17.3968* (-41.2812 to -6.6976) |

*=indicates statistically significant value (p < 0>

Supplementary Table 3: Influenza and CVD-related Age-Adjusted Mortality Rates per 1,000,000, Stratified by Race in Adults in the United States 1999-2023

| Age Adjusted Rates (95% CI) | |||||

| Year | NH American Indian or Alaskan Native | NH Asian or Pacific Islander | NH Black or African American | NH White | Hispanic or Latino |

| 1999 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Unreliable(3.79 to 12.8) | 6.7(4.99 to 8.81) | 12.02(11.27 to 12.78) | 6.72(4.43 to 9.78) |

| 2000 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Unreliable(2.62 to 10.04) | 6.12(4.49 to 8.13) | 12.66(11.89 to 13.43) | 6.24(3.96 to 9.37) |

| 2001 | Unreliable(0 to 0) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Unreliable(1.03 to 3.03) | 1.75(1.47 to 2.04) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) |

| 2002 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Unreliable(1.05 to 3.09) | 4.59(4.13 to 5.05) | Unreliable(0.96 to 3.97) |

| 2003 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | 4.82(3.43 to 6.59) | 10.57(9.88 to 11.27) | 3.86(2.29 to 6.1) |

| 2004 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | 3.77(2.58 to 5.32) | 7.3(6.73 to 7.87) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) |

| 2005 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | 4.24(2.97 to 5.87) | 10.66(9.98 to 11.34) | 3.59(2.19 to 5.54) |

| 2006 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Unreliable(0.74 to 2.5) | 4.92(4.46 to 5.38) | Unreliable(0.83 to 3.18) |

| 2007 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | 2.13(1.83 to 2.43) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) |

| 2008 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | 4.67(3.38 to 6.3) | 9.3(8.68 to 9.92) | 2.94(1.74 to 4.65) |

| 2009 | Unreliable(10.84 to 34.8) | 5.61(3.67 to 8.23) | 6.3(4.93 to 7.94) | 7.05(6.5 to 7.6) | 11.75(9.6 to 13.9) |

| 2010 | Unreliable(0 to 0) | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | 1.73(1.06 to 2.67) | 1.4(1.16 to 1.64) | 2.69(1.69 to 4.07) |

| 2011 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Unreliable(1.51 to 5.1) | 4.39(3.22 to 5.83) | 5.33(4.87 to 5.79) | 4.38(3.12 to 5.99) |

| 2012 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Unreliable(1.3 to 4.66) | 2.9(1.97 to 4.12) | 4.82(4.39 to 5.26) | Unreliable(1.29 to 3.43) |

| 2013 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | 10.49(7.74 to 13.91) | 11.31(9.35 to 13.27) | 15.23(14.46 to 16) | 10.99(8.84 to 13.14) |

| 2014 | Unreliable(9.26 to 29.74) | 8.12(5.88 to 10.94) | 13.12(11.06 to 15.18) | 16.07(15.27 to 16.86) | 15.6(13.21 to 17.98) |

| 2015 | 36.7(23.51 to 54.6) | 13.84(10.85 to 17.41) | 14.22(12.02 to 16.43) | 24.84(23.87 to 25.8) | 11.39(9.27 to 13.51) |

| 2016 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | 8.44(6.23 to 11.19) | 8.36(6.81 to 9.92) | 10.54(9.9 to 11.18) | 10.33(8.42 to 12.23) |

| 2017 | Unreliable(11.17 to 32.91) | 18.36(14.92 to 21.79) | 18.77(16.32 to 21.22) | 29.09(28.06 to 30.12) | 20.51(17.85 to 23.17) |

| 2018 | 51.81(36.84 to 70.82) | 32.22(27.81 to 36.62) | 38.91(35.49 to 42.34) | 50.94(49.58 to 52.31) | 31.28(28.08 to 34.48) |

| 2019 | 41.44(29.02 to 57.36) | 15.65(12.72 to 18.58) | 20.9(18.45 to 23.36) | 23.5(22.57 to 24.43) | 17.61(15.31 to 19.91) |

| 2020 | 35.11(24.17 to 49.3) | 26.98(23.23 to 30.73) | 42.14(38.73 to 45.54) | 23.94(23.01 to 24.88) | 35.37(32.19 to 38.54) |

| 2021 | Suppressed(Suppressed to Suppressed) | Unreliable(1.34 to 3.81) | 4.73(3.65 to 6.03) | 3.54(3.18 to 3.9) | 4.38(3.32 to 5.68) |

| 2022 | 47.7(34.79 to 63.83) | 12.75(10.29 to 15.61) | 25.1(22.46 to 27.75) | 28.99(27.97 to 30.01) | 22.06(19.59 to 24.53) |

| 2023 | 31.52(21.27 to 45) | 8.66(6.7 to 11.02) | 19.24(16.94 to 21.53) | 20.13(19.28 to 20.98) | 16.56(14.45 to 18.68) |

Supplementary Table 4: Overall and Sex‐Stratified Influenza and CVD–related Age-Adjusted Mortality Rates per 1,000,000 in Adults in the United States 1999-2023

| Age Adjusted Rates (95% CI) | |||

| year | Female | Male | Overall |

| 1999 | 10.6 (9.78 to 11.41) | 12.6 (11.38 to 13.83) | 11.4 (10.72 to 12.08) |

| 2000 | 11.13 (10.29 to 11.96) | 12.38 (11.2 to 13.57) | 11.71 (11.03 to 12.4) |

| 2001 | 1.7 (1.37 to 2.03) | 1.66 (1.27 to 2.13) | 1.74 (1.48 to 2) |

| 2002 | 4.01 (3.52 to 4.5) | 4.48 (3.78 to 5.18) | 4.25 (3.84 to 4.66) |

| 2003 | 9.16 (8.41 to 9.9) | 10.42 (9.37 to 11.47) | 9.71 (9.1 to 10.32) |

| 2004 | 6.06 (5.46 to 6.67) | 7.55 (6.66 to 8.44) | 6.64 (6.14 to 7.14) |

| 2005 | 9.37 (8.64 to 10.11) | 10.1 (9.08 to 11.12) | 9.71 (9.11 to 10.31) |

| 2006 | 3.91 (3.43 to 4.39) | 5.2 (4.49 to 5.92) | 4.39 (3.99 to 4.79) |

| 2007 | 1.74 (1.42 to 2.06) | 2.41 (1.94 to 2.89) | 2.01 (1.75 to 2.28) |

| 2008 | 7.65 (7 to 8.31) | 9.68 (8.74 to 10.63) | 8.43 (7.89 to 8.96) |

| 2009 | 6.85 (6.21 to 7.49) | 8.4 (7.61 to 9.2) | 7.53 (7.03 to 8.02) |

| 2010 | 1.36 (1.09 to 1.67) | 1.72 (1.37 to 2.12) | 1.48 (1.27 to 1.7) |

| x2011 | 4.86 (4.34 to 5.37) | 5.58 (4.91 to 6.24) | 5.19 (4.78 to 5.59) |

| 2012 | 3.99 (3.53 to 4.44) | 5.19 (4.54 to 5.84) | 4.44 (4.06 to 4.81) |

| 2013 | 12.58 (11.78 to 13.39) | 17.11 (15.96 to 18.27) | 14.46 (13.79 to 15.13) |

| 2014 | 13.3 (12.45 to 14.14) | 18.51 (17.36 to 19.66) | 15.55 (14.87 to 16.24) |

| 2015 | 21.16 (20.14 to 22.19) | 25 (23.62 to 26.37) | 22.78 (21.96 to 23.6) |

| 2016 | 8.48 (7.82 to 9.14) | 12.67 (11.74 to 13.61) | 10.26 (9.71 to 10.81) |

| 2017 | 24.65 (23.56 to 25.75) | 30.36 (28.9 to 31.83) | 27.09 (26.21 to 27.97) |

| 2018 | 42.22 (40.79 to 43.64) | 54.75 (52.83 to 56.67) | 47.55 (46.4 to 48.7) |

| 2019 | 19.97 (18.99 to 20.95) | 25.61 (24.33 to 26.89) | 22.54 (21.76 to 23.33) |

| 2020 | 22.89 (21.84 to 23.94) | 32.86 (31.44 to 34.28) | 27.42 (26.56 to 28.28) |

| Total | 11.95 (11.78 to 12.13) | 15.74 (15.5 to 15.98) | 13.53 (13.39 to 13.67) |

| 2021 | 3.2 (2.81 to 3.6) | 4.23 (3.72 to 4.75) | 3.68 (3.36 to 3.99) |

| 2022 | 25.3 (24.22 to 26.39) | 29.86 (28.5 to 31.23) | 27.3 (26.46 to 28.15) |

| 2023 | 17.86 (16.94 to 18.77) | 20.96 (19.83 to 22.09) | 19.35 (18.64 to 20.07) |

| Total | 15.68 (15.18 to 16.18) | 18.57 (17.95 to 19.19) | 16.98 (16.59 to 17.37) |

Supplementary Table 5: Influenza and CVD-related Age-Adjusted Mortality Rate per 1,000,000 Stratified by Census Region in Adults in the United States 1999-2023

| Age Adjusted Rates (95% CI) | ||||

| Year | Northeast | Midwest | South | West |

| 1999 | 8.43 (7.17 to 9.69) | 17.4 (15.7 to 19.1) | 8.32 (7.33 to 9.31) | 12.33 (10.73 to 13.94) |

| 2000 | 9.01 (7.71 to 10.3) | 17.4 (15.71 to 19.1) | 9.94 (8.86 to 11.01) | 10.74 (9.26 to 12.23) |

| 2001 | 1.21 (0.78 to 1.78) | 1.78 (1.29 to 2.41) | 1.52 (1.14 to 2) | 2.5 (1.85 to 3.3) |

| 2002 | 3.18 (2.47 to 4.03) | 6.87 (5.82 to 7.91) | 3.25 (2.65 to 3.86) | 3.79 (2.98 to 4.75) |

| 2003 | 5.49 (4.5 to 6.48) | 14.54 (13.02 to 16.07) | 8.93 (7.94 to 9.92) | 9.54 (8.2 to 10.89) |

| 2004 | 6.98 (5.88 to 8.09) | 10.23 (8.97 to 11.5) | 5.16 (4.41 to 5.9) | 4.12 (3.3 to 5.09) |

| 2005 | 9.45 (8.18 to 10.73) | 17.66 (16.02 to 19.31) | 6.42 (5.59 to 7.25) | 5.86 (4.84 to 6.89) |

| 2006 | 4.07 (3.27 to 5) | 6.05 (5.09 to 7.02) | 3.68 (3.06 to 4.29) | 3.94 (3.15 to 4.85) |

| 2007 | 2.03 (1.49 to 2.7) | 2.29 (1.74 to 2.95) | 1.53 (1.17 to 1.98) | 2.27 (1.7 to 2.98) |

| 2008 | 6.7 (5.65 to 7.75) | 13.9 (12.48 to 15.32) | 7.11 (6.27 to 7.94) | 5.96 (4.97 to 6.95) |

| 2009 | 5.91 (4.91 to 6.91) | 6.5 (5.52 to 7.47) | 6.17 (5.42 to 6.91) | 12.19 (10.84 to 13.55) |

| 2010 | 0.85 (0.52 to 1.32) | 1.11 (0.75 to 1.57) | 2.19 (1.78 to 2.68) | 1.35 (0.93 to 1.89) |

| 2011 | 5.19 (4.29 to 6.08) | 5.28 (4.43 to 6.13) | 5.15 (4.47 to 5.83) | 4.93 (4.08 to 5.79) |

| 2012 | 3.19 (2.54 to 3.96) | 6.31 (5.39 to 7.24) | 4.17 (3.56 to 4.78) | 4.02 (3.24 to 4.8) |

| 2013 | 15.19 (13.65 to 16.72) | 19.3 (17.69 to 20.92) | 11.36 (10.38 to 12.34) | 13.58 (12.19 to 14.98) |

| 2014 | 12.72 (11.31 to 14.13) | 19.03 (17.42 to 20.64) | 16.54 (15.38 to 17.71) | 12.59 (11.28 to 13.89) |

| 2015 | 30.12 (27.99 to 32.24) | 27.98 (26.05 to 29.91) | 19.24 (17.99 to 20.5) | 16.23 (14.74 to 17.72) |

| 2016 | 9.29 (8.1 to 10.49) | 9.95 (8.8 to 11.11) | 8.13 (7.33 to 8.93) | 15.01 (13.59 to 16.42) |

| 2017 | 21.21 (19.45 to 22.96) | 32.42 (30.36 to 34.47) | 22.77 (21.44 to 24.09) | 33.77 (31.68 to 35.87) |

| 2018 | 41.8 (39.34 to 44.25) | 55.31 (52.66 to 57.97) | 45.4 (43.55 to 47.25) | 47.41 (44.96 to 49.86) |

| 2019 | 22.69 (20.86 to 24.52) | 22.5 (20.81 to 24.2) | 21.26 (20.02 to 22.51) | 24.47 (22.74 to 26.2) |

| 2020 | 43.61 (41.08 to 46.14) | 24.47 (22.71 to 26.23) | 24.24 (22.92 to 25.55) | 22.02 (20.4 to 23.64) |

| Total | 13.03 (12.72 to 13.34) | 16.03 (15.7 to 16.35) | 12.15 (11.93 to 12.37) | 13.44 (13.13 to 13.74) |

| 2021 | 2.36 (1.81 to 3.01) | 2.62 (2.07 to 3.26) | 5.92 (5.26 to 6.59) | 1.98 (1.52 to 2.54) |

| 2022 | 24.57 (22.72 to 26.42) | 29.51 (27.58 to 31.44) | 27.47 (26.09 to 28.85) | 27.1 (25.31 to 28.89) |

| 2023 | 19.35 (17.69 to 21.01) | 17.5 (16.02 to 18.97) | 20.5 (19.31 to 21.69) | 18.73 (17.25 to 20.2) |

| Total | 15.57 (14.71 to 16.43) | 16.75 (15.91 to 17.6) | 18.17 (17.51 to 18.82) | 16.18 (15.37 to 16.98) |

Supplementary Table 6: Influenza and CVD-related Age-Adjusted Mortality Rates per 1,000,000 in the Metropolitan and Non-metropolitan areas in Adults in the United States 1999-2020

| Age Adjusted Rates (95% CI) | ||

| Year | Metro | Non-Metro |

| 1999 | 9.33 (8.64 to 10.01) | 19.75 (17.72 to 21.78) |

| 2000 | 9.92 (9.22 to 10.62) | 19.15 (17.15 to 21.14) |

| 2001 | 1.38 (1.12 to 1.64) | 3.09 (2.34 to 4) |

| 2002 | 3.31 (2.92 to 3.71) | 8.17 (6.87 to 9.46) |

| 2003 | 8.17 (7.55 to 8.79) | 16.29 (14.47 to 18.1) |

| 2004 | 5.98 (5.45 to 6.5) | 9.46 (8.08 to 10.84) |

| 2005 | 7.88 (7.28 to 8.48) | 17.74 (15.87 to 19.62) |

| 2006 | 3.82 (3.41 to 4.23) | 6.91 (5.74 to 8.07) |

| 2007 | 1.75 (1.48 to 2.03) | 3.07 (2.36 to 3.93) |

| 2008 | 6.74 (6.21 to 7.27) | 16.02 (14.28 to 17.76) |

| 2009 | 7.07 (6.55 to 7.6) | 9.59 (8.23 to 10.95) |

| 2010 | 1.27 (1.04 to 1.49) | 2.71 (2.04 to 3.51) |

| 2011 | 4.8 (4.37 to 5.22) | 6.94 (5.81 to 8.06) |

| 2012 | 3.51 (3.15 to 3.88) | 8.82 (7.56 to 10.08) |

| 2013 | 13.28 (12.57 to 13.98) | 20.33 (18.43 to 22.22) |

| 2014 | 14.46 (13.74 to 15.19) | 21.12 (19.17 to 23.07) |

| 2015 | 21.3 (20.43 to 22.17) | 29.9 (27.61 to 32.18) |

| 2016 | 10 (9.41 to 10.59) | 11.94 (10.47 to 13.41) |

| 2017 | 25.22 (24.29 to 26.15) | 36.33 (33.83 to 38.82) |

| 2018 | 44.19 (42.97 to 45.4) | 64.57 (61.27 to 67.88) |

| 2019 | 20.63 (19.81 to 21.45) | 32.47 (30.13 to 34.82) |

| 2020 | 26.81 (25.89 to 27.74) | 30.74 (28.45 to 33.04) |

| Total | 12.46 (12.31 to 12.61) | 18.66 (18.27 to 19.06) |

Supplementary Table 7: Influenza and CVD–related Age-Adjusted Mortality Rates per 1,000,000, Stratified by States in Adults in the United States 1999-2020

| State | Age Adjusted Rates (95% CI) |

| Alabama | 11.54 (10.49 to 12.59) |

| Alaska | 12.5 (8.8 to 17.23) |

| Arizona | 10.04 (9.19 to 10.89) |

| Arkansas | 15.9 (14.36 to 17.45) |

| California | 12.18 (11.77 to 12.59) |

| Colorado | 16.74 (15.38 to 18.1) |

| Connecticut | 13.25 (12.04 to 14.45) |

| Delaware | 11.76 (9.47 to 14.44) |

| District of Columbia | 5.72 (3.77 to 8.32) |

| Florida | 6.82 (6.45 to 7.18) |

| Georgia | 8.84 (8.11 to 9.57) |

| Hawaii | 11.25 (9.41 to 13.1) |

| Idaho | 22.19 (19.54 to 24.85) |

| Illinois | 10.58 (9.96 to 11.2) |

| Indiana | 16.88 (15.78 to 17.98) |

| Iowa | 21.24 (19.62 to 22.86) |

| Kansas | 18.42 (16.75 to 20.09) |

| Kentucky | 17.72 (16.33 to 19.1) |

| Louisiana | 8.39 (7.44 to 9.34) |

| Maine | 20.08 (17.69 to 22.48) |

| Maryland | 11.29 (10.32 to 12.27) |

| Massachusetts | 12.67 (11.78 to 13.56) |

| Michigan | 12.97 (12.21 to 13.73) |

| Minnesota | 21.53 (20.2 to 22.87) |

| Mississippi | 13.98 (12.47 to 15.49) |

| Missouri | 16.78 (15.68 to 17.88) |

| Montana | 24.14 (20.97 to 27.32) |

| Nebraska | 25.22 (22.81 to 27.62) |

| Nevada | 7.55 (6.34 to 8.77) |

| New Hampshire | 16.04 (13.73 to 18.35) |

| New Jersey | 7.91 (7.29 to 8.53) |

| New Mexico | 11.92 (10.24 to 13.59) |

| New York | 14.09 (13.53 to 14.64) |

| North Carolina | 14.47 (13.61 to 15.33) |

| North Dakota | 24.86 (21.13 to 28.59) |

| Ohio | 13.63 (12.92 to 14.33) |

| Oklahoma | 21.79 (20.15 to 23.42) |

| Oregon | 16.74 (15.37 to 18.11) |

| Pennsylvania | 12.48 (11.88 to 13.09) |

| Rhode Island | 21.95 (19.13 to 24.78) |

| South Carolina | 17.32 (15.99 to 18.65) |

| South Dakota | 33.64 (29.64 to 37.63) |

| Tennessee | 15.19 (14.13 to 16.26) |

| Texas | 13.77 (13.2 to 14.34) |

| Utah | 12.6 (10.84 to 14.37) |

| Vermont | 24.89 (20.85 to 28.94) |

| Virginia | 10.95 (10.12 to 11.78) |

| Washington | 18.33 (17.18 to 19.48) |

| West Virginia | 22.36 (20.16 to 24.55) |

| Wisconsin | 19.1 (17.91 to 20.29) |

| Wyoming | 19.5 (15.59 to 24.08) |

| Total | 13.53 (13.39 to 13.67) |

Supplementary Table 8: Influenza and CVD-related Mortality, Stratified by Place of Death in Adults in the United States 1999-2023

| Deaths | |||

| Year | Medical Facility - Inpatient | Decedent's home | Nursing home/long term care |

| 1999 | 462 | 157 | 379 |

| 2000 | 536 | 186 | 309 |

| 2001 | 61 | 41 | 41 |

| 2002 | 184 | 56 | 159 |

| 2003 | 527 | 119 | 266 |

| 2004 | 375 | 81 | 182 |

| 2005 | 501 | 106 | 337 |

| 2006 | 265 | 63 | 114 |

| 2007 | 103 | 47 | 52 |

| 2008 | 500 | 126 | 234 |

| 2009 | 612 | 129 | 55 |

| 2010 | 113 | 37 | 12 |

| 2011 | 402 | 59 | 128 |

| 2012 | 318 | 62 | 115 |

| 2013 | 1017 | 232 | 376 |

| 2014 | 1364 | 216 | 226 |

| 2015 | 1719 | 232 | 721 |

| 2016 | 1003 | 153 | 99 |

| 2017 | 2337 | 355 | 624 |

| 2018 | 4025 | 858 | 1017 |

| 2019 | 2154 | 368 | 346 |

| 2020 | 2314 | 955 | 310 |

| 2021 | 329 | 92 | 30 |

| 2022 | 2546 | 590 | 373 |

| 2023 | 1767 | 434 | 281 |

| Total | 25534 | 5754 | 6786 |

Supplementary Table 9: Influenza and CVD–related Age-Adjusted Mortality Rates per 1,000,000, Stratified by States in Adults in the United States 1999-2020 ranked according to Percentiles.

| State | Deaths | Age Adjusted Rate | Rank | Percentile |

| South Dakota | 278 | 33.64 | 1 | 100 |

| Nebraska | 429 | 25.22 | 2 | 98 |

| Vermont | 147 | 24.89 | 3 | 96 |

| North Dakota | 176 | 24.86 | 4 | 94 |

| Montana | 225 | 24.14 | 5 | 92 |

| West Virginia | 402 | 22.36 | 6 | 90 |

| Idaho | 271 | 22.19 | 7 | 88 |

| Rhode Island | 238 | 21.95 | 8 | 86 |

| Oklahoma | 686 | 21.79 | 9 | 84 |

| Minnesota | 1019 | 21.53 | 10 | 82 |

| Iowa | 673 | 21.24 | 11 | 80 |

| Maine | 272 | 20.08 | 12 | 78 |

| Wyoming | 87 | 19.5 | 13 | 76 |

| Wisconsin | 1000 | 19.1 | 14 | 74 |

| Kansas | 475 | 18.42 | 15 | 72 |

| Washington | 992 | 18.33 | 16 | 70 |

| Kentucky | 639 | 17.72 | 17 | 68 |

| South Carolina | 663 | 17.32 | 18 | 66 |

| Indiana | 913 | 16.88 | 19 | 64 |

| Missouri | 900 | 16.78 | 20 | 62 |

| Colorado | 595 | 16.74 | 21 | 58 |

| Oregon | 578 | 16.74 | 21 | 58 |

| New Hampshire | 187 | 16.04 | 23 | 56 |

| Arkansas | 410 | 15.9 | 24 | 54 |

| Tennessee | 792 | 15.19 | 25 | 52 |

| North Carolina | 1102 | 14.47 | 26 | 50 |

| New York | 2470 | 14.09 | 27 | 48 |

| Mississippi | 333 | 13.98 | 28 | 46 |

| Texas | 2303 | 13.77 | 29 | 44 |

| Ohio | 1431 | 13.63 | 30 | 42 |

| Connecticut | 472 | 13.25 | 31 | 40 |

| Michigan | 1133 | 12.97 | 32 | 38 |

| Massachusetts | 795 | 12.67 | 33 | 36 |

| Utah | 198 | 12.6 | 34 | 34 |

| Alaska | 42 | 12.5 | 35 | 32 |

| Pennsylvania | 1643 | 12.48 | 36 | 30 |

| California | 3446 | 12.18 | 37 | 28 |

| New Mexico | 196 | 11.92 | 38 | 26 |

| Delaware | 92 | 11.76 | 39 | 24 |

| Alabama | 468 | 11.54 | 40 | 22 |

| Maryland | 519 | 11.29 | 41 | 20 |

| Hawaii | 146 | 11.25 | 42 | 18 |

| Virginia | 674 | 10.95 | 43 | 16 |

| Illinois | 1132 | 10.58 | 44 | 14 |

| Arizona | 540 | 10.04 | 45 | 12 |

| Georgia | 583 | 8.84 | 46 | 10 |

| Louisiana | 306 | 8.39 | 47 | 8 |

| New Jersey | 632 | 7.91 | 48 | 6 |

| Nevada | 155 | 7.55 | 49 | 4 |

| Florida | 1375 | 6.82 | 50 | 2 |

| District of Columbia | 27 | 5.72 | 51 | 0 |

References

- Properzi S, Santolini G, Bonanno E, Giacchetta I, de Waure C. Influenza’s burden: an umbrella review about complications, hospitalizations and mortality. Eur J Public Health 2023;33.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Langer J, Welch VL, Moran MM, Cane A, Lopez SMC, Srivastava A, et al. High Clinical Burden of Influenza Disease in Adults Aged ≥ 65 Years: Can We Do Better? A Systematic Literature Review. Adv Ther 2023;40:1601–27

Publisher | Google Scholor - Skaarup KG, Modin D, Nielsen L, Jensen JUS, Biering-Sørensen T. Influenza and cardiovascular disease pathophysiology: strings attached. European Heart Journal Supplements 2023;25:A5–11.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jaiswal V, Ang SP, Yaqoob S, Ishak A, Chia JE, Nasir YM, et al. Cardioprotective effects of influenza vaccination among patients with established cardiovascular disease or at high cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022;29:1881–92.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dashtban A, Mizani M, Rafferty S, Pasea L, Tomlinson C, Mu Y, et al. Association of COVID-19 and influenza vaccinations and cardiovascular drugs with hospitalisation and mortality in COVID-19 and Long COVID: 2-year follow-up of 17 million individuals in England. Eur Heart J 2024;45.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). CDC WONDER. Retrieved February 7, 2025.

Publisher | Google Scholor - U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). Geographic levels. Retrieved February 7, 2025.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. (2024). NCHS urban-rural classification scheme for counties. Retrieved February 7, 2025.

Publisher | Google Scholor - National Cancer Institute. (n.d.). Joinpoint Regression Program [Software]. Retrieved February 7, 2025.

Publisher | Google Scholor - El-Horbaty, Y. S., & Hanafy, E. M. (2024). A Monte Carlo permutation procedure for testing variance components using robust estimation methods. Statistical Papers, 65(1), 335–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00362-023-01396-2

Publisher | Google Scholor - Watson L, Qi S, DeIure A, et al. Using autoregressive integrated moving average (Arima) modelling to forecast symptom complexity in an ambulatory oncology clinic: harnessing predictive analytics and patient-reported outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(16): 8365.[12]

Publisher | Google Scholor - D Modin, B Claggett, N D Johansen, S D Solomon, R Trebbien, T G Krause, J U S Jensen, C J M Martel, M P Andersen, G Gislason, T Biering-Soerensen, Excess mortality and hospitalizations associated with seasonal influenza in patients with heart failure, European Heart Journal, Volume 45, Issue Supplement_1, October 2024, ehae666.923, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae666.923

Publisher | Google Scholor - Skaarup KG, Modin D, Nielsen L, Jensen JUS, Biering-Sørensen T. Influenza and cardiovascular disease pathophysiology: strings attached. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2023 Feb 14;25(Suppl A):A5-A11. doi: 10.1093/eurheartjsupp/suac117. PMID: 36937370; PMCID: PMC10021500.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Modin, D, Claggett, B, Johansen, N. et al. Excess Mortality and Hospitalizations Associated With Seasonal Influenza in Patients With Heart Failure. JACC. 2024 Dec, 84 (25) 2460–2467.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2024.08.048

Publisher | Google Scholor - Phelopater Sedrak, Vera Dounaevskaia, G.B.John Mancini, Shelley Zieroth, Robert S. McKelvie, Wynne Chiu, David Bewick, Anique Ducharme, Samer Mansour, Serge Lepage, Glen J. Pearson, Robert C. Welsh, Jacob A. Udell, Kim A. Connelly, Vaccination in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: A Case-Based Approach and Contemporary Review, CJC Open, 10.1016/j.cjco.2025.09.004, (2025).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jiaxue Fan, Qin Wang, Ying Deng, Junyan Liang, Hua You, Role of Illness Perception in Explanation of Influenza Vaccination Intention and Behavior in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: A Cross-Sectional Survey, American Journal of Health Promotion, 10.1177/08901171251356270, (2025)

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ouranos K, Vassilopoulos S, Vassilopoulos A, Shehadeh F, Mylonakis E. Cumulative incidence and mortality rate of cardiovascular complications due to laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2024;e2497. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2497

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hailun Yin, Wenjuan Wu, Yuyang Lv, Hanlin Kou, Yuzhen Sun, Comparative Evaluation of Three Rapid Influenza Diagnostic Tests for Detection of Influenza A and B Viruses Using RT‐PCR as Reference Method, Journal of Medical Virology, 10.1002/jmv.70162, 97, 1, (2025).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Florien S. van Royen, Roderick P. Venekamp, Patricia C.J.L. Bruijning-Verhagen, Frans H. Rutten, Acute Respiratory Infections Fuel Cardiovascular Disease, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.10.079, 84, 25, (2468-2470), (2024).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Derqui N, Nealon J, Mira-Iglesias A, Díez-Domingo J, Mahé C, Chaves SS. Predictors of influenza severity among hospitalized adults with laboratory confirmed influenza: analysis of nine influenza seasons from the Valencia region, Spain. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2022;16:862–872.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Alling DW, Blackwelder WC, Stuart-Harris CH. A study of excess mortality during influenza epidemics in the United States, 1968–1976. Am J Epidemiol 1981;113:30–43.

Publisher | Google Scholor - 21. Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, Chung H, Crowcroft NS, Karnauchow T, Katz K, Ko DT, McGeer AJ, McNally D, Richardson DC, Rosella LC, Simor A, Smieja M, Zahariadis G, Gubbay JB. Acute Myocardial Infarction after Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Infection. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 25;378(4):345-353. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702090. PMID: 29365305.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chow EJ, Rolfes MA, O’Halloran A, Anderson EJ, Bennett NM, Billing Let al. Acute cardiovascular events associated with influenza in hospitalized adults. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:605–613.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Biasco L, Klersy C, Beretta GS, Valgimigli M, Valotta A, Gabutti Let al. Comparative frequency and prognostic impact of myocardial injury in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and influenza. Eur Heart J Open 2021;1:oeab025

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sellers SA, Hagan RS, Hayden FG, Fischer WA. The hidden burden of influenza: a review of the extra-pulmonary complications of influenza infection. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2017;11:372–393

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wu Y, Huang H. Synergistic enhancement of matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression and pro-inflammatory cytokines by influenza virus infection and oxidized-LDL treatment in human endothelial cells. Exp Ther Med 2017;14:4579–4585.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet. 2018; 391(10127): 1285-1300. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)33293-2

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kyung-Teak Park, Minjea Choi, Jun Hyung KimKi-Woon Kang. (2024) Cardio-cerebrovascular adverse outcomes in patients with influenza with and without preexisting cardiovascular disease: Oral antiviral agents impact. Medicine 103:29, pages e39032.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Behrouzi B, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, et al. Association of Influenza Vaccination With Cardiovascular Risk: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e228873. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.8873

Publisher | Google Scholor

Alcrut

Alcrut